Street Scamming in Beijing

Its Methods and the Overall Context of Fraud in China

Christopher Clayton

05/22/2012

INTRODUCTION

This paper explores scamming or scam-like street activities in Beijing. It focuses on tea-house and related environments, rickshaws, and art. It can be argued that some of this is not really scamming due to services provided, especially in the case of art. However it is included due to the way sellers present these services and try to overcharge on them, or because of misrepresentation of products. From the data, it is possible to see how tea houses vary in what they charge, but they typically either quote or get away with large sums in any case. Rickshaw prices in these situations tend to be lower and more consistent. Art price data can be more varied as well, based on size, but ultimately the sellers target one nominal price range, even if initial offers before haggling are higher. It also explores the tricks scammers use and suggestions for how to stay out of situations, or ways to defuse them if ensnared.

BACKGROUND

The basis for this paper arose from the author's trip to Beijing in September 2011. The author interacted with people who used different methods of selling services or products on the street. However, the author went along with different interactions with these commercial aspects to them out of having some money to experiment with, and out of not fully understanding some scam mechanics.

Therefore in spite of showing and sending feelings of not liking the interactions and feeling awkward, the author was led to two different establishments on two occasions, and in the first instance was not told what kind of venue it was. It was a fully-furnished tea-house in a closed room, and the author left as quickly as possible after realizing the situation. In the second instance the author became much more adamant about going into a room at all and asked about room charges, but still did not think to ask about menus. This was on the upper floor of a commercial rental space in a much more barren closed room, and the establishment served juice. The author also dealt with one group of aggressive rickshaw drivers twice, as well as an art "professor" and one of his "students" who were separated by a few blocks. They were supposedly planning an exhibition to take place California. The student's room was on the upper floor of a commercial rental space, and the professor in an upper-floor office. A third student was encountered as well which resulted in an art gallery visit.

In this way the trip resulted in data which provides clues as to how much Chinese citizens on the street, either with genuinely friendly feelings alongside their fraudulent actions or fully-feigned friendliness, are able to overcharge tourists. The scope of this part of the paper is thus concerned with Chinese citizens scamming foreigners, rather than Chinese citizens scamming other Chinese citizens. However the paper also explores these types of scams for comparison, and how damaging they can be. These include scam phone calls and other kinds of street scams, on the national level but with international elements as well, and smaller operations in various cities.

The author's data is presented alongside data from peoples' reported experiences on the Internet, in blogs and message boards. Qualitative descriptions make use of these situations, as well as the author's experiences.

STATISTICAL METHODS AND DATA

Besides the author's price data from experience, online data is used, i.e. from discussion forums. From this, averages and variances for different data-sets are calculated. Beijing and more specifically its tourist areas (Wangfujin, etc.) serve as the scope of the study, as the author only has data for that city due to having experienced only a few scam attempts in Shanghai and Suzhou, and having come away with little to no price samples. The price data is split into US dollar and Chinese yuan columns, with real current values for both currencies in another two columns. These real current values are used to find real current averages and variances for each data set to provide information on price consistency for the sample data.

For data analysis, first, one known currency is converted into the unreported one for the time period by using that period's exchange rate in order to provide both nominal values. The period is roughly the month and year. The beginning of a quarter is used if only a rough date within the year can be accurately estimated. I.e., this includes forums posts that do not mention specific months of being cheated, but one can go by the date of posting. Otherwise the rate for January is used if any estimation of a month at all is suspect. X-Rates.com was used to obtain this exchange rate data for calculations. The consumer price index for the time-period regarding both currencies is then found, and along with this the modern CPI (in this case, the end of 2011), and these nominal price values are used to find the current real value of both currencies. Using the average for all of the data points for a particular currency, the real value variance is calculated for that currency. Offered potential scam prices are used because that was the intended sale price of the sellers, but actual price paid through haggling or other means is reported as well.

A mutual base CPI is used for both countries (2005), so the period of interest is 2005 to the relative present (end of 2011). Some earlier scam data is supplied for comparison but is not used for variance calculation. Base CPI resets are not used, i.e. a process by which the base CPI is re-set to 100 after five years or some other period (Zhang). Instead the year 2005 is used as the only base value. CPI values are used by the year, not by the month. If a price is roughly known to have been active before the mid-point of a year (the entirety of June), the CPI for the previous year is used instead. If the quarter of the year is roughly known, the start of the quarter is used. If users provide their own exchange conversions, those are used instead of making estimated calculations based on monthly exchange rate averages.

Particularly, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data is used for the US economy. The CPI values are shifted in order to make 2005 the base year, i.e. 2006 is found by calculating 201.6 195.3 (the 2006 and 2005 CPI values according to the base-year used by the BLS), and adding this difference to 100. For the Chinese economy, National Bureau of Statistics of China data for yearly inflation increases by percentage is used, and 2005 is converted into the base year. So, to find 2006's CPI in this sense, one adds 2.81% of 100 to 100. For 2007, one adds 6.58% of 102.81 to 102.81, etc.

Real current American CPI in this sense: 129.64

Real current Chinese CPI in this sense: 122.79

Tea House Scams

These scams involve people who act friendly and strike detailed conversations which can involve flattery and pretexts of practicing English. They may have stories about why they are in Beijing to mask the fact that they are in collusion with local tea houses or other establishments in order to further lure in marks. They will suggest going to or just plain walk someone into an establishment with closed-room service at some point, whether it's a fully-decorated tea-house or part of a commercial space rental. The first warning sign is always that no menu is offered or management makes counter-claims concerning what the menu actually says at payment time.

The colluders might make fake cultural excuses for why they can't pay for their portion or why they are not obligated to pay, or may pretend to be surprised at the expense. This can make it more difficult to want to dispute charges or to haggle, out of politeness. The threat of security presence while being stuck in an enclosed room further heightens the problem. The ability to haggle is severely affected in general due to the scam transitioning from the street into a formal business setting, with many options of escape anticipated by the scammers.

It is most likely not realistic to control for time spent in a scamming tea-house or related establishment. They usually charge a large sum according to the situations encountered and studied, no matter if a mark leaves immediately or after a few hours. Amount ordered can factor in, but the prices get very high no matter what due to the colluders "ordering" an appreciable quantity, such as at least one or two whole pots of tea, plus snacks. So it also doesn't matter if the mark actually consumes much of it at all. At the same time if one can escape the persuasion of sampling a certain item that the colluders "ordered," one might escape being charged for that portion. If one even eats a small bit of that part of what was "ordered," one gets charged a lot or the waiter/proprietor at least attempts to do so, and the same for drinking one cup of tea, let alone a whole pot. The more astronomical prices take place more often in "tea ritual" situations involving multiple cups of tea and types of tea. Therefore quantity ordered is reported when possible to contextualize the value of what was purchased or offered.

Preventing the scam in the first place cannot necessarily be done passively. If one sends indirect messages of feeling awkward at being unabashedly spoken to and asked so many questions by strangers, the colluders might continue more forcefully and repeatedly comment on one's quietness or other actions. A direct statement of not being interested in tea houses can immediately stave off less forceful talkers. If one is in front of an establishment of their choosing or if tea houses come up in the conversation more directly, it's time to be more direct and verbal about not liking the situation, even if in a polite way, and it's vital to be consistent.

Even good counter-scammers can be taken off-guard, such as a 2005 or 2006 situation that took place in Shanghai (Clarke, 2011). The blog writer wasted the time of the scammer by taking her to a McDonald's for thirty minutes. However he was taken off-guard when they arrived right in front of a restaurant afterward and forgot about the risks of entering a new street acquaintance's chosen venue. The whole situation was a set-up with food already laid out and three tough "waiters" ready to enforce payment even without his eating anything.

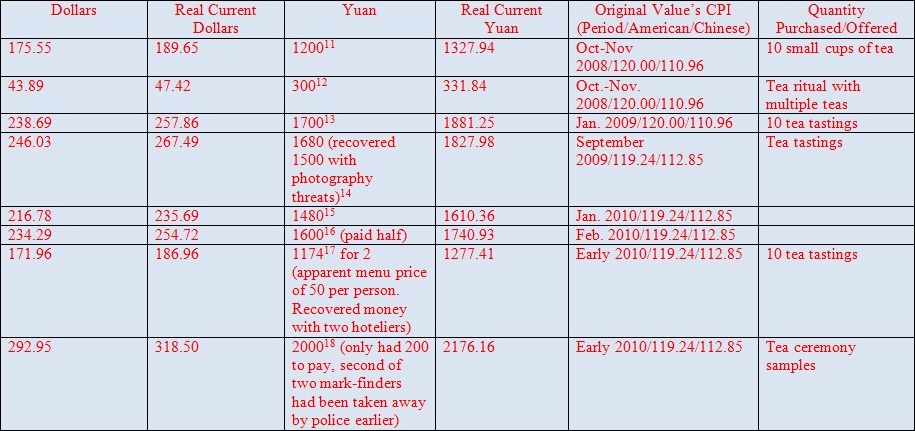

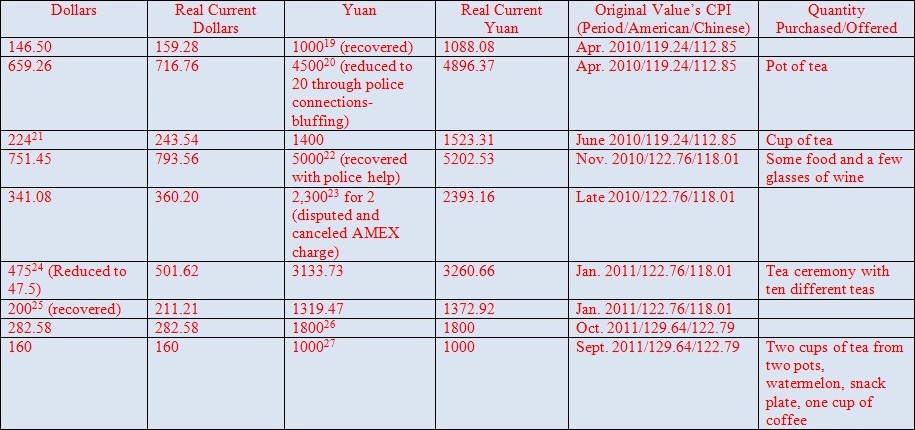

Table 1: Tea Houses/Bar Price Samples

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1. China Forums, pg. 3

2. China Forums, pg. 1

3. China Forums, pg. 1

4. Zonaeuropa

5. China Forums, pg. 4, user-provided exchange conversions in American dollars, British pounds and yuan

6. Lonely Planet Beijing Scams and Tips thread, pg. 2

7. Lonely Planet Beijing Scams and Tips thread, pg. 2

8. Lonely Planet Beijing Scams and Tips thread, pg. 2

9. Lonely Planet Beijing Scams and Tips thread, pg. 2

10. China Forums, pg. 10

11. Lonely Planet Beijing Tea House Ceremony Scam thread, pg. 1

12. China Forums, pg. 10

13. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

14. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

15. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

16. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

17. Lonely Planet Beijing tea house scam thread, pg. 1

18. China Forums, pg. 12

19. Rumination and Reflection blog

20. China Forums, pg. 12

21. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting, user-provided exchange conversion from yuan to American dollars

22. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

23. Lonely Planet Beijing tea house scam thread, pg. 1

24. China Forums, pg. 13

25. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

26. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

27. Author experience

28. Author experience

29. A Fish Out of Grimsby blog, user-provided exchange conversion from yuan to British pounds

Price variance between different sample situations is high, but in general tea houses try to obtain 1000 yuan or more in nominal value from a mark. Various victims in these reported situations have successfully gained partial or full refunds by contacting the police, or haggling with or confronting servers/proprietors by themselves. One can see that in general, the nominal price for a pot of a standard tea brew should only be about 20 yuan for what is typically offered. However, partaking in the tea or other snacks, even after looking at menu prices, can lead to claims of drinking an expensive tea or that the price was really per cup rather than per pot, etc.

Rickshaw Scams

Pedicab scams can involve roves of rickshaws or scooters looking for marks. Leaders can use deliberate lies about the price in order to sit one down on their vehicle or on one of their pack's vehicles. It might even involve being forcibly sat onto the vehicle if one gets too close, and involve sales tactics such as how nice it would be to take a break from walking. However they could drop one off in a completely different area than requested as well. Off the bat one could try and haggle if one wants the service, but politely refusing many times or expressing interest in other forms of transportation can be seen as a form of haggling too. Thus they can take the opportunity to keep talking while lowering their offered price. In the latter sense one could at least eventually stave them off. However it can be hard to ascertain whether or not they would actually keep up their end of the bargain, especially without written agreement, even in the case of non-aggressive types. That is, those ones may be persistent and attempt to go back on their word, but do not exude intimidation or force.

One can also haggle afterwards but it could be hard to get anywhere close to standard prices, especially if one is in an unfamiliar alley area where no-one would want to help one. In this way there is a continued threat. One can waste their time though by going to an ATM with the driver, if the driver suggests this, and then pretending that one's credit/debit card doesn't work with the machine, or showing that it legitimately cannot work with such machines. They will probably end up wanting something, however, especially on a return journey in which they are willing to go to one's hotel to get payment. They might even stop the vehicle and walk with one if a busier street must be used or crossed to get to the hotel. Again, there can be ever-present looming intimidation in this sense. If it's a ride to a different location, the driver may settle for less than what they want but clean out whatever money one has.

In terms of distance, the amount of service that scooters and rickshaws provide is mostly controlled for within the boundaries of interest because most of the time they only go a short distance. At least in these cases, people take a rickshaw through a hutong (inner-city neighborhood) on a one-way trip. Taxis would be controlled for distance as well as possible by only counting airport to hotel transportation situations, but they are not examined in this paper.

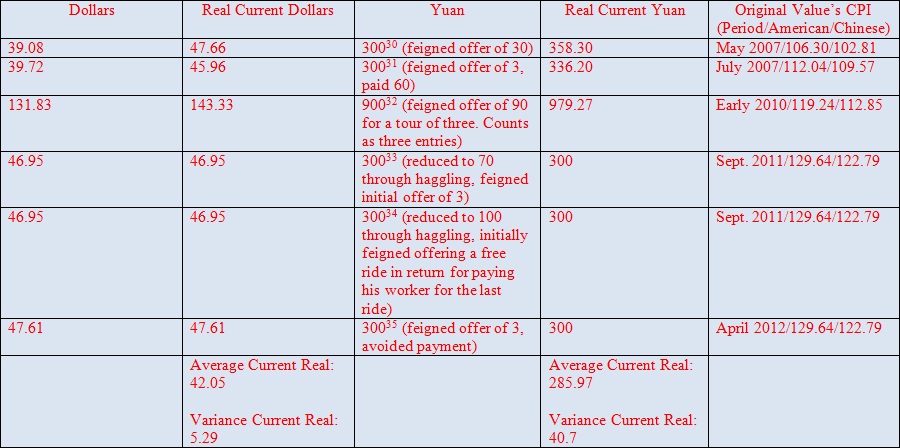

Table 2: Rickshaw Service Price Samples

30. Lonely Planet Beijing Scams and Tips thread, pg. 2

31. Virtual Tourist Beijing taxis/pedicabs review thread

32. Trip Advisor

33. Author experience

34. Author experience

35. Virtual Tourist Beijing taxis/pedicabs review thread

From the sample data, this scam consistently results in a nominal value demand of 300 yuan no matter the period, regardless of inflation. From these examples one can conclude that for the localized distances that rickshaws tend to travel, their nominal true price is really about 30 yuan. Sometimes they offer this to start, but also may say the service is only 3 yuan, which is suspiciously inexpensive. In both kinds of situations the driver will want 300 yuan and may show laminated price-sheets, only after the ride is finished, to show that it is their "established," and thus supposedly legal, rate. This is the same with tea houses keeping their own "prices" around somewhere in order to try and legitimize them. However such menus' appearances only after services are rendered de-legitimizes this. The same applies for their bringing up counter-claims concerning what the prices "really are" or bringing up price conditions that the mark "didn't understand."

Art Selling Scams

Art scams in tourist areas involve people who claim they are art students or art professors in order to pique interest. They may take one to part of a commercial rental space or even a legitimate gallery, or a legitimate office. In order to gain ground to lock in a sale, a seller may write a note in Chinese on parchment to one as a "gift," and immediately start doing it without asking. The seller may try to claim that the price offered is greatly discounted, that it would be wonderful for a foreigner to purchase their art to spread awareness of it, etc.

Real versus copied art cannot be controlled for easily except if each situation's art were appraised. It would also depend on comparing its price to the Chinese market and to the US market, and how much copies versus originals would go for in both markets. Therefore size of the art when available is provided instead, as this variable tells more about the value of the purchase or offer, even if price-inflated.

One can assume these types of products involve copies due to the way they are sold or offered. This is different from formal auction venues or other such kinds of market activity, which do not need to involve confidence-generating tricks such as sellers claiming to be preparing for an exhibition in the mark's home country. However the pricier fakes which occur from them cause much more damage, such as a portrait sold for $11m that had falsified origins exposed in 2010 (Lim, 2011).

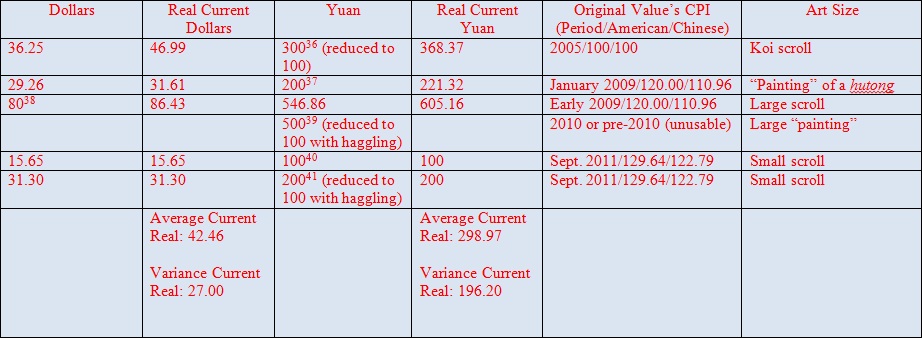

Table 3: Street-Marketed Art Price Samples

36. China Forums, pg. 3

37. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

38. Virtual Tourist Beijing art students review thread, pg. 1

39. Chinese Outpost blog Beijing Tea Scam and Variations posting

40. Author experience

41. Author experience

The author was not able to obtain much data for this type of scam, but one can conclude in general from the samples that these kinds of sellers typically wish to offload small scroll copy paintings for 100-200 yuan each. Being able to sell a larger one might simply mean greater cash flow. One can assume that ordinarily a local would pay less for these products, but it can be argued that at least in the case of smaller products, no real scam or serious scam activity takes place. There is typically no feeling of intimidation except in the form of sympathy-appealing sales tactics, such as noting the gift of calligraphy they made or that they need money to fund their exhibition trip. This is unlike being boxed into a tea-house room or being in an alley without police presence where a rickshaw driver can make demands.

GREATER CONTEXT

Even though some of these scams against foreign tourists can generate hundreds of dollars per instance, scams that target other Chinese citizens or people in other Asian countries take place on just as large or a larger scale. These scams can also have little to no legal front, unlike tea houses that also provide services at normal prices to everyone else, and not all of them involve inflated prices but rather entirely fake services or threatening demands with no substance except fear-inducement. They can end up extracting more money out of a group of people whom they may repeatedly target, and can take vaster sums from single individuals. In general they involve more criminal violations to accomplish goals rather than civil violations.

These include national and international phone scam networks that can abuse the confidence of individuals on deeper levels such as threats to family to gain money from them. Many large-scale scams are done this way, including impersonation of officials and relatives, and claims of holding relatives hostage. There are also other financial-based scams such as those involving fraudulent bank transfers, fake lotteries and high-profile fraud committed by actual officials. Other scams include ones targeting shoppers, college students and Chinese citizens generally. Further there is a recent institutional tourist industry-related issue, i.e. the mismanagement of the Forbidden City, with resulting thefts and other problems.

In this way, it is understandable how an overall pressing concern exists and tour scams against foreigners are just one part of it. Police are available as they can to help recover money for foreign tourists as can be seen from reported message board situations, even if they do not actually raid foreign-preying businesses as often to more fully improve national reputation. However, as an example of this, two tea-houses were raided in July 2007 for these activities (O'Connor, 2007).

Impersonation and Ransom Demands

Phone scam cases involving the impersonation of officials, relatives and others, and claims of having kidnapped a relative have been wide-spread and large-scale. They can have an international element to them. The cases explored all involve operations in mainland China in some way, including localized operations.

Mainland China cracked down on 229 telecommunications fraud rings with 1,400 arrests and the seizure of 12.48m yuan in the seven weeks leading to August 2009 (Xinhua, 2009). This included telephone company representative fraud in Xiamen, Haikou and Chengdu, with some scam operations targeting victims in Vietnam. In September 2010, 70% of 800m mainland phone users had pre-paid SIM cards without their real names registered, so the government began a campaign to change this in order to help combat fraud (Jiao, 2010). Beijing kiosks that sold SIM cards received a 5,000 yuan fine, and those who purchased pre-paid cards were made to use their official ID cards and register with real names. However, there was also backlash about the resulting privacy of phone conversations and text messages because of how much more easily the government could control dissenting viewpoints. In July 2011, mainland Chinese police handed over 14 Taiwanese fraudsters to Taiwan who had been captured at the end of 2010 for multinational telecom fraud (Xinhua, 2010). The original bust included the deportation of 24 total suspects from the Philippines to China, including the 14 Taiwanese ones, after joint raids. The fraud ring had targeted 20 mainland provinces for a total of about US $20m (Chung, 2011). Taiwan had voiced resentment over not receiving its own residents to begin with and had even frozen the issuance of work permits to Filipino workers for a time.

In Hong Kong, by October 2006, HK $18.22m was lost to similar scammers, compared to 2005 at HK $16.72m (Sun, Yeung, 2006). The whole year saw 1,737 total reports for a total of HK $23.21m, and 2005 saw 780 reports (Lo, 2007). By June 2007 there were 841 cases with HK $9.6m in losses, but a major syndicate of around 170 people received a blow with 16 members arrested. By November 2009 two gang leaders involved in cross-border scams between Shenzhen and Hong Kong at HK $3m had been arrested (Crawford, Hu, 2009). This involved claims of holding relatives hostage, with criminals crossing the border to collect ransoms. By September 2010, five Hong Kongers were arrested who ran a HK $23m scam involving the impersonation of mainland Chinese police officers (South China Morning Post, 2010). In the months leading to December 2010, scams involving claims of being a relative jailed in mainland China extracted HK $11m (Cheung, Lee, 2010). 2010 involved a total of HK $24m in scams. In the first ten months, there were about 1,191 telephone deceptions, only a decrease of 4% from the year before, but their success rate dropped from about 31.2% to 22.4%. Hong Kong fraudsters have also used shell businesses, such as the case of Golden Longon extracting HK $10.4m from Areva, a French nuclear energy firm, in January 2011 (Chiu, 2011). It claimed participation in joint efforts with French police to bust a credit ring in order to gain Areva's confidence.

In November 2009, 23 members of a Hsinchu-based syndicate running operations in China were busted (Central News Agency, 2009). The main activity included telecommunications representation fraud. They accrued about NT $10m in three months. In June 2010, Operation 1011 resulted in 1,000 officers from both Taiwan and China working together to make 122 arrests (Chung, 2010). 57 venues in 17 Chinese provinces and 43 venues in 12 Taiwanese counties and cities were raided, containing hardware and teaching materials aimed at recruits. Two leaders were captured along with NT $60m ready to be wired to the mainland for alleged laundering. An earlier report claimed 148 total people in police custody (Tam, 2010). 400 cross-strait cases had taken place since September 2009 at 36m yuan. Besides kidnap claim calls, cases also involved impersonations of police officers and government officials. Before this on April 4th, 47 suspects in Dongguan, Guangdong were arrested. This included 13 suspects from Taiwan and mainland suspects from six different cities. In the same month a cross-straits agreement was signed which helped make these crackdowns possible.

South Korea and China also agreed to work together on phone fraud in January 2011 (Korea Times, 2011). The scams involved police and bank official impersonations and ransom demands, with a growing network based in China suspected. Overall the scams had caused damages of around 200b won over three years, with 1,500 South Korean suspects believed to have moved operations to China over five years.

Mainland China has found success in busting impersonation and ransom scams, but has also overstepped its boundaries in terms of privacy rights. It has done joint operations with Taiwan but also incurred a diplomatic incident with them. Hong Kong tackled big scams which involved cross-border activity, but could have stood to become more creative in order to take on problems such as shell businesses and to bust more cases.

Lottery and Other Financial Scams

Other scams exist such as fake lotteries, and many of them also take place over the phone or through other electronic means such as websites. High-profile cases involving fraud by officials have also occurred.

An Anshan lottery agent figured out how to exploit software flaws in Welfare Lottery machine systems, and also had relatives cash multiple tickets for him, beginning in 2005 (Xinhua, 2008). He accrued 27m yuan total this way and was arrested by January 2007. In April 2005, a real estate company was exposed for defrauding the Bank of China out of $600m yuan with the help of two Beijing lawyers and a bank official (Ting, 2005). This was an attempt to restart the Senhao Apartment construction project in Beijing, which had stopped in early 2002. A Christchurch-focused business scam reported in May 2005 involved a Chinese e-mail campaign whose messages asked for a representative from each company targetted to come to Kunming (Cronshaw, 2005). This involved a request to bring a sample machine part as part of signing a contract to manufacture them for the requester, but this really resulted in extortion of these representatives. Between August and December 2005, a businessman fraudulently accrued 432.5m yuan in bank notes with the help of five Bank of China officials (Hu, 2006). In spite of freezing his assets, 100m yuan was still unaccounted for in March 2006. Another businessman obtained 96 bills from Heilongjiang's second largest lender in February 2006 with the help of Bank of China officials, and cashed them in other banks for 914.6m yuan (Hu, 2006). At the same time China Construction Bank was dealing with its own compliance issues. These problems also came after an early 2005 instance of a Heilongjiang bank official taking 1b yuan in client money. Chinese police cracked 49,000 financial cases in 2006 in spite of these issues, and recovered 12.94b yuan (Quek, 2006). However, cracked case success only improved by 4.3% from 2005, but 51.8% more money was recovered. One case involved a Shanghai company selling stock based on exaggerated overseas performance, raising 20m yuan from 252 people. A string of fake Credit Union Australia sites run by a Chinese gang, with at least one site hosted in Harbin, used the image of a celebrity to gain the trust of Australian Chinese in order to obtain credit card numbers in early 2010 (Bryce, 2010). This included an e-mail spam campaign. In early 2011, various fraudulent bank activities had been taking place, such as Qilu Bank's alleged involvement in $227m worth of commercial bank bills used as short-term business loans (Callick, 2011). Irregularities had come to light in a 2009 audit, and this generated an international issue due to the fact that Australia's Commonwealth Bank owned 20% of the business. Other banks in Shandong Province also came under scrutiny.

In 2005 the former CFO of Sun Cheong General Holdings appeared in court on charges of generating false invoices as part of a HK $14m scam against the Housing Authority (Gentle, 2005). Regarding lottery fraud, Hong Kong scam damages totaled HK $40m in 2008 with 653 complaints out of 1,079 total, compared to 2007 at 354 complaints and HK $19m (Tsang, 2008). Since that October a new fraud team had arrested 28 suspects allegedly involved in operations totaling HK $38m. This mainly involved Taiwanese people at 19 suspects, along with five Hong Kongers, three Malaysians and a single mainlander. A man was arrested in January 2006 for stealing $2.89m from Hang Seng Bank with the help of a forged mainland identity card and fake two-way permit to deceive bank officials into making a money transfer (Tsui, 2006). The bank ultimately took a $1m loss. 4 admitted to involvement in fraud targeting Hong Kong insurance companies in January 2007, at claims of HK $23.68m (Tsui, 2007). They were a former Hong Kong insurance agent and three mainlanders, with the scam involving participants intentionally having one of their eyes damaged in the mainland to file accident claims in Hong Kong. Honglong and Shanghai Banking Corporation lost US $1b in December 2008 to Madoff's investment redistribution scam (Yin, 2009). A woman pled guilty in January 2009 to successfully convincing a teller to fraudulently transfer HK $2.6m from an HSBC bank account to her Hang Seng account by providing enough details about the HSBC account (Fong, 2009). She had been impersonating another woman, who noticed suspicious activity and reported it in September 2008. Two other suspects were on the run at the time of the court hearing. In April 2009 the launderers for a HK $20m lottery scam operation were sentenced (Man, 2009). Victims included Chinese people in Japan and Singapore. In May 2009, 10 were jailed in a HK $13.88m lottery scam targeting 12 overseas Chinese (Lam, 2009). A Hong Kong lawyer appeared in court in October 2009 over alleged loan fraud against the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (Fong, 2009). This involved two mortgage loans of HK $10.9m obtained between June 2005 and July 2006. August 2009 saw an undercover raid on eight financial companies with 17 arrests of Hong Kong residents concerning aggressive loan sharking (Mok, 2009). 13 Hong Kongers were arrested for lottery fraud gang activity in June 2010 (Straits Times, 2010). Their operation included 160 Chinese victims in Malaysia, Singapore, China, Taiwan, Australia and New Zealand, at HK $21m. In June 2010, 20 state ministries and government agencies were exposed in creating fake invoices to dodge taxes, maintain illegal petty cash accounts and otherwise misuse public funds (Li, 2010). This totaled HK $162m and was exposed by the National Audit Office. Street versions of Mark Six lottery frauds have occurred, such as cases in 2010 totaling HK $182,700, with payments of $2000 to $50,000 from individual victims (Cheung, 2010). It involved altering the dates of genuine Jockey Club tickets with previously-winning numbers. These types of street scams were reported about 50 times for the first 10 months of the year. In May 2011 Hong Kong police began investigating a Mark Six lottery website run by mainlanders claiming to be Hong Kong officials (Moy, 2011). This also included a fake press conference presented by three people claiming to have Hong Kong government and Jockey Club-approved tip-off technology. Fees involved 900 to 13,800 yuan per victim. 300 residents of Guangzhou, mostly small and medium-sized enterprise owners, protested in the streets over high debt payments demanded by guarantee firms (Xinhua, 2012). This generated a police response of 180 officers and government investigation. The two firms had helped secure loans from banks, but the banks demanded direct payment from business owners for everything. The firms kept much of the loans unreleased for financing programs, and one of them was allegedly involved in up to 1.7b yuan in bad loans.

A 2005 case involved fraudsters impersonating the Shandong-based Hua Tai Group, with text messages to Singaporeans claiming they had won a lucky draw (Ho, 2005). This included a "prize" of $130,000 and a request for $3,900 in "government taxes" per victim. The same fraudsters also operated in Taiwan, and extracted $650,000 from a graduate student with a "prize" offer of $4.5m. In November 2008, five members of the phone lottery fraud group Hong Kong China Trust Group were busted by Singaporean and Taiwanese commercial affairs enforcers in a joint operation (Quek, 2008). The group had hired mainland Chinese citizens to do phone work and kept 90% of its gains at its headquarters in China, rather than in Taiwan. Part of their target group included Singaporeans with "prizes" offered of HK $60,000. Eight Singaporeans who had been fooled into giving S $85,000 total helped bust them with an initial police report.

China has also had success with these other kinds of phone scams and financial scams, but at one point did not improve much on cases cracked. There were also problems with the corruption of officials, especially bank-related fraudsters, even if they were found and prosecuted. Hong Kong further suffered from cases of unrecoverable bank monetary losses. Aggressive big business practices have inflamed smaller business owners in the South China area because of banks, even if investigations occurred.

Shopping, Education and Other Scams

Various other scams take place in China as well. This includes education-related fraud, retail fraud and street scams targeting Chinese citizens.

In July 2007, an official involved in taking bribes to ensure unqualified students could sit for the national college entrance exam in June was captured in Hefei (Xinhua, 2007). This involved 24,000 yuan received from teachers and 747 unqualified students receiving certificates to attend. Another scam involved the selling of passing test results to students who had failed. Police managed to arrest four people in Dangshan who had offered 41 students 1,000 yuan each to participate. The operation also involved an Anhui University student (Li, 2007). That student was offered 300,000 yuan to recruit students for test-taking, and they could also earn up to 10,000 yuan total from the initial offer of 1,000 based on performance. In July 2008 the police arrested five leaders organizing activity in Gansu Province, which included 31 illegal exam takers (Xinhua, 2008). Police and universities were able to stop 2,645 cheaters out of 10.38m total examinees in China, an increase of 800 from 2007. In August 2010, a senior middle school ghost exam operation by Zhoupu Middle School in Wuhan was exposed (South China Morning Post, 2010). This involved 32 pupils, not necessarily with their awareness. Middle schools had motivation to push drop-outs through the system in this way because they received 1,500 yuan per year for each student who continued education. This was part of an incentive program for job creation.

In August 2011, Forbidden City workers were reported for allegedly admitting some tourists into the Palace Museum without their having to pay for tickets (Jiao, 2011). Guides and museum guards also allegedly took various ticket fees directly for themselves. A person who video-taped instances of these activities tried to bribe these workers for 200,000 yuan, but ultimately accepted 100,000 which they took from the financial department (MacKinnon reports an acceptance of 80,000 in exchange for information which cracked the case, which would imply negotiations with management instead). Only one temporary worker was punished. These practices are significant as the museum made 590m yuan in 2010 from 12.83m visitors, meaning workers and management have large responsibilities that they haven't fulfilled. Other issues in 2011 included the theft of jewelry on loan from a private Hong Kong museum, the pressure-washing of the Celadon Plate into six pieces, the discovery that 100 out of 200,000 rare books were missing with orders that staff not investigate, and the discovery that eight paintings were missing (MacKinnon, 2011). There was also controversy over the unavailability of the Palace of Established Happiness to public entrance; the accusation by a former Bank of China official that the Museum evaded taxes on tickets sold for exhibitions outside the main gate; and the 1997 purchase of five Song letters because they were sold for three times the purchasing price in 2005, which Internet users exposed.

Mainlanders represented a large percentage of street scammers in Hong Kong at the beginning of 2007 (Kwong, 2007). 53 of 57 arrested suspects from 30 solved 2005 cases out of 393 were mainlanders. 29 out of 30 arrested suspects from 21 solved cases out of 201 from 2006's first 11 months were also mainlanders. Overpriced and fake commodity reports reached 100 in April 2007, the highest concentration of reports in a single month known as of then (Wu, 2007). 400 officers were assigned to make authenticity checks, including 100 in a single operation. In that month, in the weeks leading to Golden Week beginning on May 1st, customs officers went undercover and also interviewed possible mainland victims in Shandong and Hebei Provinces (Connolly, 2007). The Travel Industry Council also extended the tourist purchase refund period from 14 days to 180 days (Eng, 2007). Beijing-Hong Kong joint operations were also planned, with inspectors disguised as tourists sent to keep tour operations honest (Cai, 2007). The China National Tourism Administration further planned to create tour standards, including transparent information concerning the hotel used by the tour, shops on the routes traveled and time allocated for shopping. High-ticket items of questionable authenticity bought by mainland tourists included a HK $9,800 diamond pendant from Expo Global and a HK $16,800 Seclus watch from Majestic Watch & Jewelry Company. In 2008, from January to September, there were 184 reported street-scam cases with 23 arrests at HK $4.43m in damages (But, 2008). This included cell-phone cash "borrowing" scams at 97 cases for the first half of the year, and 23 in counterfeit electronics. There were also spiritual blessing scams. This involves giving an item to be blessed, which is then replaced with a relatively worthless item that is wrapped up. The victim is told not to unwrap it for some time. In 2011 there were 43 total cases, an increase of 18 from 2010 (Lau, 2012). Total street-scam reports increased to 102 in 2011 with HK $6m losses, up from 62 in 2010 and HK $3.2m losses. Arrests fell from 22 to 14, with police putting blame on the fact that many scammers were mainlanders who quickly jumped the border.

Educational fraud cases were handled by China with good outcomes, but again, in the first place this involved issues with officials themselves. The management of the Forbidden City also established a poor reputation for itself. However, Hong Kong and China have worked together to create anti-fraud tactics against retailers. At the same time Hong Kong has had issues maintaining arrest rates of street scam artists, suggesting more fluid cross-border collaboration is needed in that sense.

CONCLUSION

Tea house scams by far attempt to collect the most money in terms of street scams against foreign tourists, and use a variety of tricks in order to do so. However it is possible to try and talk one's way out of some or much of the cost, and to also try to obtain police, hotelier or local help after the event to get money back. Rickshaws consistently demand similar nominal fees, and they can be aggressive but if one is caught up in taking the service, haggling politely afterwards can help soften the monetary blow. Typical art scams tend to involve the level of fees that one could safely haggle a rogue rickshaw driver down to, but do not typically carry the same feeling of intimidation, just sales tactics.

These represent only a few of the scams that China has to deal with, however. Operations in surrounding nations employ Chinese nationals to work scams for them as well, so it not only involves local scammers and their lackeys. In this way China has had a variety of fraudulent economic activity to deal with and much of it. Especially when the fraud involves officials or executives, this represents a greater threat to the nation than dealing with possible foreign reputation hits. These scams also target fellow Chinese citizens as well which demands the primary attention of authorities.

In terms of busting large operations, China has been able to do so and has worked with other nations for that purpose. However it has also had to clean its own government of corrupt elements and their partners outside of government, particularly in bank-related problems, even if it has had success with such high-profile cases. There are also outstanding management issues with the Forbidden City. Hong Kong has had particular problems controlling street scams and its banks have seen unnecessary monetary loss before, in spite of creating many anti-fraud tactics with the mainland in respect to the retail industry.

NEWS REFERENCES

Bryce, Jason, "Chinese online bank scam using TV personality's face," Sunday Territorian (Australia) (14 February 2010): LexisNexis.

But, Joshua, "Police to seek tougher penalties for scams," South China Morning Post (26 September 2008): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Cai, Jane, "Beijing joins crackdown on tour scams," South China Morning Post (26 April 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Callick, Rowan, "Chinese bank scams vindicate local claims," The Australian (18 January 2011): LexisNexis.

Central News Agency, "Police bust cross-strait scam ring in central Taiwan," Central News Agency (26 November 2009): Taipei, LexisNexis.

Cheung, Simpson; Lee, Ada, "Police alarmed at success rate of new phone scam," South China Morning Post (31 December 2010): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Cheung, Simpson, "Warning of Mark Six scam," South China Morning Post (31 December 2010): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Chiu, Austin, "French firm fooled by phone scam," South China Morning Post (29 September 2011): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Connolly, Norma, "Customs to go undercover on shopping scams," South China Morning Post (18 April 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Chung, Lawrence, "Beijing to hand over 14 fraud suspects to island; Manila angered Taipei by deporting the Taiwanese to the mainland in February with 12 mainlanders," South China Morning Post (27 May 2011): Taipei, LexisNexis.

Chung, Lawrence, "Taiwan police praise cross-strait co-operation on phone scammers," South China Morning Post (24 June 2010): Taipei, LexisNexis.

Cronshaw, Tim, "Chinese scam targets NZ firms," The Press (Christchurch, New Zealand) (24 May 2005): Christchurch, LexisNexis.

Eng, Dennis, "Shops must give tourists refunds up to 6 months," South China Morning Post (18 April 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Fong, Loretta, "Not guilty plea over HK $10.9m loan scam," South China Morning Post (20 October 2009): LexisNexis.

Fong, Loretta, "Bank account milked of HK $2.6m," South China Morning Post (3 January 2009): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Gentle, Nick, "$14m taken in invoice scam," South China Morning Post (9 August 2005): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Ho, Chua Kong, "Send Money Scam; China conmen have come up with an SMS version of lucky-draw scams, and they are targeting Singaporeans," The Straits Times (Singapore) (27 March 2012): Singapore, LexisNexis.

Hu, Bei, "Police put clamps on bank bill scammer," South China Morning Post (15 March 2006): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Hu, Bei, "Banks not moving fast enough to stem fraud," South China Morning Post (10 March 2006): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Jiao, Priscilla, "Forbidden City in new scandal over ticket scam," South China Morning Post (11 August 2011): LexisNexis.

Jiao, Priscilla, "National registration aims to foil phone scammers; Pre-paid SIM cards lose their anonymity," South China Morning Post (1 September 2010): LexisNexis.

Korea Times, "Korean, Chinese prosecutors to cooperate in busting phone scams," Korea Times (25 January 2011): LexisNexis.

Kwong, Robin, "Most street scam artists come from mainland," South China Morning Post (11 January 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Lam, Anita, "10 jailed for crude lottery scam," South China Morning Post (14 May 2009): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Lau, Stuart, "Street swindlers evading justice," South China Morning Post (30 January 2012): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Lim, Louisa, "In China's Red-Hot Market, Fraud Abounds," NPR (11 October 2011): NPR.org.

Li, Raymond, "Auditor reveals 142m yuan fake invoice scam," South China Morning Post (24 June 2010): LexisNexis.

Li, Raymond, "Crackdown over exam scam in Gansu," South China Morning Post (25 June 2008): LexisNexis.

Li, Ramond, "Four arrested for trying to hire students to sit entrance exams," South Cina Morning Post (22 June 2007): LexisNexis.

Lo, Clifford, "Police crack city's biggest phone-scam syndicate," South China Morning Post (7 June 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

MacKinnon, Mark, "Lapses at Forbidden City bring shame," The Globe and Mail (Canada) (1 September 2011): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Man, Joyce, "Taiwanese man and girlfriend jailed for role in lottery scam," South China Morning Post (7 April 2009): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Mok, Danny, "17 arrested over loan shark scams," South China Morning Post (28 August 2009): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Moy, Patsy, "Mark Six tip-offs' scam fakes official approval," South China Morning Post (8 May 2011): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Quek, Carolyn, "Lottery phone scam: 5 Taiwanese nabbed," The Straits Times (Singapore) (22 November 2008): Singapore, LexisNexis.

Quek, Tracy, "More falling prey to get-rich-quick scams," The Straits Times (Singapore) (24 November 2006): Beijing, LexisNexis.

South China Morning Post, "Phone scam suspects arrested," South China Morning Post (26 September 2010): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

South China Morning Post, "Phantoms boost school exam results," South China Morning Post (30 August 2010): LexisNexis.

Straits Times, "Singaporeans among HK scam victims," The Straits Times (Singapore) (28 June 2010): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Sun, Celine; Yeung, Winnie, "Elderly targeted as phone scams soar," South China Morning Post (10 October 2006): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Tam, Fiona, "148 held in cross-strait phone-scams crackdown," South China Morning Post (22 June 2010): LexisNexis.

Ting, Shi, "Another huge fraud rocks Bank of China," South China Morning Post (3 April 2005): LexisNexis.

Tsang, Phyllis, "Police team assigned to fight lottery fraud after scams totaling HK $40m this year," South China Morning Post (1 December 2008): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Tsui, Yvonne, "32 months in jail for bank scam," South China Morning Post (12 April 2006): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Wu, Helen, "Customs reveals rise in complaints over shopping scams, fake goods," South China Morning Post (6 May 2007): Hong Kong, LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "Protests against loan scams in south China city," Xinhua News Agency (27 March 2012): LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "China police hand over 14 Taiwanese telephone scam suspects," Xinhua News Agency (6 July 2011): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "Chinese police detain 1,400 people in telephone scams," Xinhua News Agency (31 July 2009): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "Three police officers accused of corruption in Chinese college exam scam," Xinhua News Agency (5 July 2008): Lanzhou, LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "Chinese man gets life sentence for 3.7m-dollar lottery scam," Xinhua News Agency (11 March 2008): Beijing, LexisNexis.

Xinhua, "Chinese police arrest official linked to college exam scam," Xinhua News Agency (12 July 2007): Shijiazhuang, LexisNexis.

WEBSITE REFERENCES

Baker, Mark, "The Beijing Tea Scam and Variations," Chinese Outpost blog (June 2006): accessed 19 May 2012, <http://blog.chineseoutpost.com/2006/06/26/the-beijing-tea-scam-variations-traveler-beware/>.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Consumer Price Index (CPI)," United States Department of Labor (2012): accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.bls.gov/cpi/>.

Clarke, Daniel, "Tourist Scams: The Beijing Tea House Scam," Living and Working in China blog (11 December 2011): accessed 21 May 2012, <http://working-in-china.com/2011/12/01/tourist-scams-the-beijing-tea-house-scam/>.

Chinese-forums.com, "The Beijing Tea Scam," Chinese-forums.com (2 April 2006): pp. 1-14, accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.chinese-forums.com/index.php?/topic/8181-the-beijing-tea-scam-and-a-few-others/>.

Haldar, Nilanshuk, "Photos and Beijing tea house scam," Rumination and Reflection blog (11 April 2010): accessed 19 May 2012, <http://nilanshuk.blogspot.com/2010/04/photos-of-beijing-tea-house-scam.html>.

Inflation.edu, "Historic inflation China," Triami Media BV and HomeFinance (2012): accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/china/historic-inflation/cpi-inflation-china.aspx>.

Lonely Planet, "Beijing Scams and Tips," Lonely Planet forums (13 June 2007): pp. 1-2, accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/thorntree/thread.jspa?threadID=1397673>.

Lonely Planet, "Beijing tea house scam," Lonely Planet forums (18 December 2010): pp. 1-2, accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.lonelyplanet.com/thorntree/thread.jspa?threadID=1899000>.

O'Connor, Maureen, "Police Raid Scam-Artist Teahouse," Shanghai List (13 July 2007): accessed 21 May 2012, <http://shanghaiist.com/2007/07/13/police_raid_sca.php>.

Virtual Tourist, "Art Students, Beijing," Virtual Tourist (20 April 2003): pp. 1-2, <http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Asia/China/Beijing_Shi/Beijing-1024960/Tourist_Traps-Beijing-Art_Students-BR-1.html>.

accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Asia/China/Beijing_Shi/Beijing-1024960/Tourist_Traps-Beijing-Art_Students-BR-1.html>.

Virtual Tourist, "Taxis/Rickshaws, Beijing," Virtual Tourist (24 August 2002): pp. 1-3, accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.virtualtourist.com/travel/Asia/China/Beijing_Shi/Beijing-1024960/Tourist_Traps-Beijing-TaxisRickshaws-BR-1.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2005," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2005.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2006," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2006.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2007," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2007.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2008," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2008.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2009," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2009.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2010," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2010.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2011," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2011.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Chinese Yuan, American Dollar) 2012," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/CNY/USD/hist2012.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (British Pound, American Dollar) 2011," X-Rates: accessed 21 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/GBP/USD/hist2011.html>.

X-Rates.com, "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (British Pound, American Dollar) 2006," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/GBP/USD/hist2006.html>.

X-Rates.com: "Monthly Exchange Rate Average (Euro, American Dollar) 2007," X-Rates: accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.x-rates.com/d/EUR/USD/hist2007.html>.

Zhang, Dongyou, "Improvement in Real GDP Estimation Approach by Production Approach," OECD: pp. 1-10, OECD.org.

Zonaeuropa.com, "How I Was a Chinese Traitor," Zona Europa (21 April 2006): accessed 19 May 2012, <http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20060521_1.htm>.